"Gods of Mexico": Indigenous Culture Exalted At The Art House

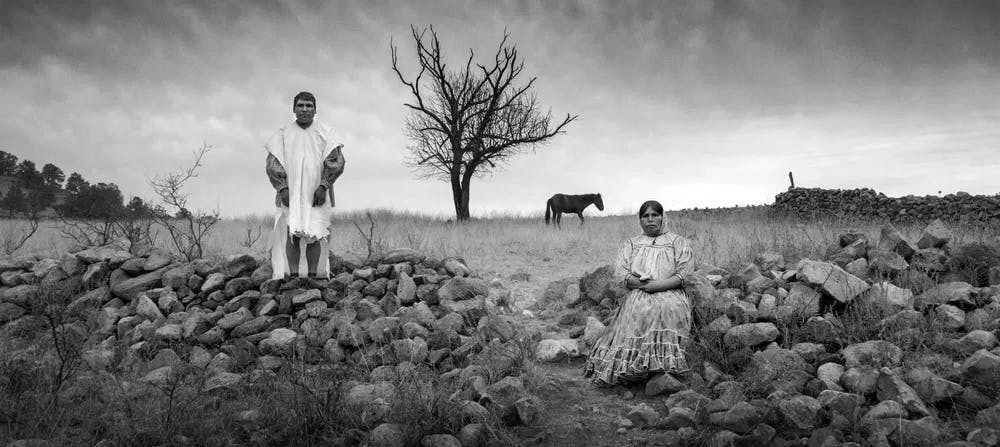

Ethnography gets imbued with sublime visual poetry in Gods of Mexico, Helmut Dosantos’ marvelous look at aboriginal culture. He fashions striking sequences of men and women at work, taking their livelihood from nature using techniques inherited from their ancestors. Beautiful colors arise as they harvest salt from the soil or go underground to toil in a mine. Just as you settle in for the ride, Dosantos throws you a curveball, cutting to sequences of portraits of people from all over the country, captured in striking black and white images. Think of tableaux vivant or old prints of Christian saints. Wes Anderson would love it. It does not look like a low budget film. And does not sound like one, either.

We spoke with Dosantos as the movie makes a staggered release in major US cities. Catch it on the big screen if you can. Every self-respecting film buff should.

Popflick: Where does the idea of Gods of Mexico come from?

Helmut Dosantos: In 2013, I was scouting for another film. I shot one of those black-and-white tableaux as research material. Suddenly, all these ideas started to come up. I connected the dots of what I had seen in my first three years and a half in Mexico. I arrived in 2009, and I noticed many different rural worlds coexisting at the same time. I have traveled the country extensively and have always been interested in rurality, peasants, fishermen, ancient societies, and archaic traditions. Doing that first image, I thought of doing a medium-length feature film of black and white portraits of indigenous people from all over the country. Then I realized I was not giving them their due. It just was not enough if I wanted to portray the deepest Mexico.

I needed to show daily labor and those cycles repeating themselves over generations. I decided to add two more chapters. There’s the Salt Mine sequence. The origins of this salt-extraction method are pre-hispanic. Still, there is a lot of syncretism with practices brought along by the colonizers, some techniques used in the Mediterranean, like when it comes to lime extraction. It takes 40 or 45 days to build it, although it seems like two days!

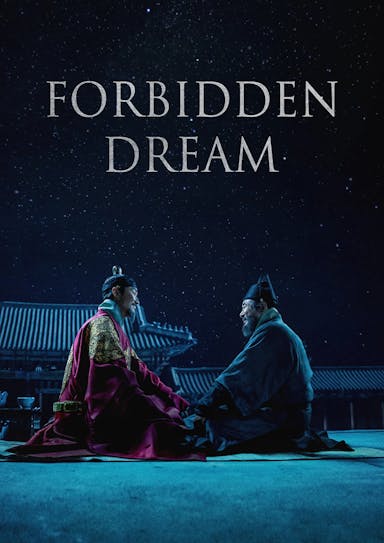

The human and the divine: a couple takes a break in "Gods of Mexico" / Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Labs.

Popflick: You switch between two very different styles. From active, immersive narrative in full color to non-narrative contemplation in black and white. Were you at all concerned about losing your audience?

Helmut Dosantos: That was the challenge. I have a lot of faith in our spectators. They can appreciate our proposal to combine different techniques. It’s not that this has not been done already, but this way of watching all these communities in Mexico, not just as an archaic manifestation, may have some novelty. The idea is to use black and white in these portraits to recognize the distance between our urbanite world and this rural, archaic world. They try to preserve themselves without losing their cultural identity.

We also divide the movie into four parts, each named after a cardinal point. The structure transmits the idea of space and how the phenomenon is geographically widespread. And I hold them like fixed portraits to give each one about 30 seconds. Each image allows your eye to go around the screen, to take in that this human being is unique in their natural space. The offscreen sounds are part of it, too. Gods of Mexico belongs in theaters, where sounds can surround you. We did an ATMOS sound mix, so you get the sound from the back and above your head.

Portraits of survival: a couple gazes at the camera in "Gods of Mexico" / Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Labs.

Popflick: The title suggests a divine quality in the subjects. And I must confess the portraits’ format reminded me of Christian saint stamps. Does that strip people of some of their humanity?

Helmut Dosantos: I always ask myself if I was operating from the point of view of an antique cosmogony or not. In olden times, and even now, rural communities keep seeing the world this way: everything comes from a single being. It divided itself little by little until becoming a dual being, masculine and feminine, and from that came all the other divinities that created the universe. Men, animals, things, everything is somewhat imbued by the divine. That is why you see a constant celebration of life, of existence in all its manifestations in these communities. They celebrate and give thanks for everything. Every time they do a new activity or labor, they have rituals to thank nature’s elements, the gods, and everything in life. So, this is a movie that celebrates life.

Popflick: Mexico is so big and with so many ethnic groups. How did you establish limits? You could have spent your whole life gathering footage.

Helmut Dosantos: Geography was determinant. I could have stayed in Oaxaca, which has an impressive amount of ethnic groups, but we wanted to portray ethnic groups from all over the country without focusing on a single state. We ended up with 23 groups, including African descendants and Mexican indigenous. Sixty-eight groups are officially recognized as such, and we covered about a third. I tried to highlight the least portrayed communities, those with less contact with projects of this kind.

The color from beneath the earth: a miner underground in "Gods of Mexico" / Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Labs.

Popflick: The epilogue in the underground mine must have been very challenging to film. How did you manage to do it?

Helmut Dosantos: I found that antimony mine while scouting for another project. It is used in alloy with other metals to make micro-circuits and stuff like that. And you can find it in bullets and women’s shoe heels! It was important for the US during World War II. You can only find pure antimony in such abundance in China. So, it was important strategically to win WWII. The mine is about 160 years old. It has 18 different levels, going down in a spiral. It has 200 kilometers of tunnels!

Popflick: Did you use a different camera to shoot underground?

Helmut Dosantos: Not really. Mostly, we used the same camera, a Canon SE200 built for war zones. It is very resistant, light, and versatile. The batteries last a long time. It also registers a wide color range. It was perfect for this kind of job. We used good, professional lenses. And obviously, lighting. There was no electricity, so we had to carry portable generators, lamps, and tripods. Without the miner’s help, we would not have been able to shoot at all. We did three different shootings, adding up to about three months underground.

Spirits of the river: "Gods of Mexico" contemplates the human and the divine. / Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Labs.

Popflick: Production took place over ten years, with three different teams and three different cinematographers in 14 shooting trips. Was it hard to keep the integrity of your vision in these conditions?

Helmut Dosantos: Not really. I think we were able to establish a consistent visual style throughout. We were precise about aesthetics from the very beginning. We were all doing the same movie. Nobody went out on his own. If you are clear about what you want, everybody works in the same direction.

Popflick: How do you feel about the finished product? Did you show everything you wanted to show?

Helmut Dosantos: I think so. I could have kept shooting, but there comes a moment when you just have to stop.

Popflick: How did you realize that moment had arrived?

Helmut Dosantos: We planned two more trips, but by then, I was already editing and realized I had enough material to articulate a complete, harmonious discourse. To keep shooting might have brought some improvements, but it would not be necessary. It would have made us spend energy, time, and resources. Climate change threw a wrench in the process, too. We were supposed to shoot in a tropical jungle with gum harvesters, but the rain was sparse that year. Therefore, there would be hardly any activity. Maybe that was the sign we had to stop!

Heaven on earth: a man is coddled by a lover and the elements in "Gods of Mexico" / Photo courtesy of Oscilloscope Labs.

Popflick: You are an Italian filmmaker making a very Mexican movie. How did that happen?

Helmut Dosantos: I have lived out of my country for over half my life. I studied in France, went to a film school in Czechoslovakia, and a bit in Cuba. I lived for a stretch in the US and then moved to Mexico because I love the country. There is even some common ground between Italy and our Mediterranean culture. We have rural worlds, the relationship people have with the land. It is very universal. I am also passionate about indigenous culture and archaic ways of life that somehow stay alive. It is reduced to folklore in Italy and Europe, but in Mexico, it is still alive. It is still your parents’ culture. They are preserving their cultural identity. It is a worthy endeavor to register it before it fades away.

Watch “Curiosity and Control”

A documentary that explores our complex relationship with nature itself and our contradictory behavior of caging what we fear may be lost.

Stream NowWant to get an email when we publish new content?

Subscribe today