The Indie Movie Gospel According to Roger Corman, Pope of Pop Cinema

Even if you have not seen a Roger Corman production, chances are his work has defined your film diet in ways we can quite fathom. Bertrand Tressier's documentary "Roger Corman, The Pope of Pop Cinema," shed some light on his influence. It is a killer primer on the career of this producer and true to the spirit of his indie movies: cheap, thoroughly entertaining, and short enough to do its job and leave you wanting more.

Director Bertrand Tressier has a long career producing and directing film-related documentaries in his native France. He also writes biographies of figures like director Jean-Pierre Melville and actor Patrick Deware. Only one of his many books is available in English via Amazon, "Judy Garland: Splendor and Downfall of a Legend."

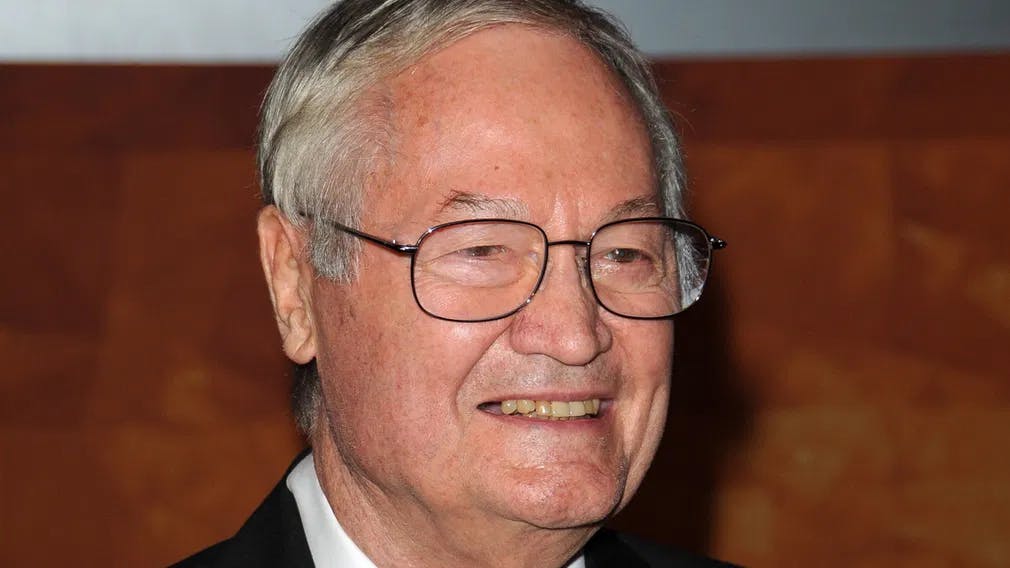

Perhaps because he comes from a foreign culture, Tessier pitches his Roger Corman documentary to the biggest audience possible. If you don't know anything about him, it will bring you up to date on the filmmaker and his particular role in the movie industry. If you are a Corman devotee, you will relish the extensive interview clips with this living institution of American Cinema, who turns out to be a genial, self-deprecating storyteller.

Engineering a Hollywood Maverick

"Roger Corman: The Pope of Cinema" covers his early fascination with film and how he turned his back on a career in engineering to follow his path into show business. He started as a messenger boy at Fox Studios and rose to script reader. Stifled off credit on a script, he took his payment to self-finance his directorial debut: "The Beast with a Million Eyes" (1955). It set the template for his career: make low budget movies in popular genres and turn a nifty return in the process. And what a career it has been! According to IMDB, in 68 years, the man has amassed over 500 credits as a producer and 56 as a director. A new action movie, "Crime City," is in the works. It will be his 513th film produced. Good luck to whoever aims to do a retrospective of his career.

Tressier's documentary is conservative in form, with plenty of movie clips and archive photos. Talking-head interviews of key collaborators drive the narrative. We meet the wife and co-producer Julie Corman, but also more recognizable filmmakers who got their first shot behind the camera in Corman films, like Allan Arkush, Joe Dante, and Oscar-winner Ron Howard.

There is nothing further from Corman's oeuvre than Academy-sanctioned, mainstream, tasteful films like Howard's "A Beautiful Mind" (2001), which earned twin statuettes for Best Film and Director. He would not have this without Corman.

By the time Howard came into the Corman fold, he already was a successful actor with almost two decades of experience, a hit show on TV - "Happy Days" (1974) - and a film directing degree from the University of Southern California. Even with such a stacked resume, no studio would take him seriously. His work for Corman tipped the scales. Howard starred in the race car action comedy "Eat My Dust" (1976). Once it became a hit, he conditioned his participation on a sequel of getting the directing gig besides starring in it. Corman agreed, and "Grand Theft Auto" (1977) effectively launched TV's own Opie as a movie director.

Corman's New Hollywood Film Lab

Howard is not the only big-name director who benefited from Corman's laboratory of ragtag cinema. Martin Scorcese made his feature film debut, "Boxcar Bertha" (1972), for him. Francis Ford Coppola took the reins of horror quickie "Dementia 13" (1968), and five years later, he was helming big studio production "Finian's Rainbow" (1973). It was a box-office failure and proved to be one of the last nails in the coffin of the golden age of big-screen musicals.

Still, the point is that the Corman way not only made Coppola a viable craftsman in the eyes of the industry, but it also convinced him of the importance of independence from the studio system. Eventually, he used the clout earned from "The Godfather" (1972) and its sequel "The Godfather Part II" (1974) to launch his studio, American Zoetrope. Coppola's penchant for ambitious, big-budgeted projects diverted from the frugality of the Corman ethos and ultimately doomed this particular enterprise. Still, at 83 years old, Coppola is now self-producing and financing the eagerly-awaited "Megalopolis." It is hard not to see Corman's influence in this dramatic gesture.

It is a shame we don't have Coppola in "Roger Corman: The Pope of Pop Cinema." At least, Howard is generous at sharing testimony of Corman's influence on the A-list. Howard may have had many advantages when he got his directorial break. Still, the Corman laboratory also pushed true blue outsiders to take their place behind the camera, some of which are at hand to provide colorful anecdotes and insights.

Allan Arkush and Joe Dante parlayed their gig as trailer editors into directing the self-referential B-movie satire "Hollywood Boulevard" (1976). Arkush's film career peaked early with "Rock 'n' Roll High School" (1979), another Corman's joint, but went on to a prolific career as an episodic TV director. Dante hit the big time with the cult classic "The Howling" (1981) and box-office sensation "Gremlins" (1984). His biggest hit proves how Corman's sensibilities seeped into the mainstream.

The list of talents that got their start under Corman is long: Jack Nicholson got an attention-grabbing cameo in "Little Shop of Horrors" (1960), and director John Sayles wrote "Piranha" (Joe Dante, 1980). And while talking about killer fish, James Cameron's feature film debut was "Piranha II: Spawning" (1982). Yes, the man who gave us the high-tech, ultra-expensive "Avatar" franchise learned the ropes in Corman's Poverty Row. The amount of talent that went through the Corman grindhouse is so large that it would be necessary to produce a whole series to fit everyone.

A Man Ahead of His Times

Arkush and Dante are great, but the most eloquent expert on Corman is himself. You feel a charming cognitive dissonance in realizing this handsome, elegant elder with a velvety voice is the mastermind behind such joyful, unapologetic shlock. If we can learn anything from Corman's low budget movies, the pleasure principle trumps highfalutin aesthetics and cultural prejudices. If you enjoy a movie, it does not matter if the actors can't act or if you can see the zipper on the monster's costume.

His films exist out of the realm of decency and good taste. He never pitched to fancy film festivals. Watching the movies he shepherded, you learn to appreciate their ingenuity at making lemonade out of lemons. They make the exercise of cinematic arts something approachable and possible to engage in by everyone. You can do it without big budgets and powerful studios. The sons and daughters of Corman are everywhere. His influence is evident, even in filmmakers who never worked under his wings. There would not be a Quentin Tarantino or Robert Rodriguez without Corman.

Social media is ripe with reports of dismayed teachers or classic film fans sharing their grief over encountering young audiences all too glad to share their disdain for anything they see onscreen that predates contemporary popular cinema. Corman films may be even more vulnerable. They wear their precariousness on their sleeve. Still, one of the most compelling insights of the movie underlines how Hollywood co-opted Corman's themes and style, juicing it up with all the bells and whistles multi-million dollar budgets can buy. What is Steven Spielberg's "Jaws" (1975), if not a creature-feature programmer with better special effects and a virtuoso behind the camera?

"Roger Corman: The Godfather of Pop Cinema" defines how style is determined by the forces of technology, commerce, and culture. Quality is relative. Corman's biggest talent was his ability to contemplate the market in front of him and craft products that would work best to attract audiences while minimizing risk. A fascinating chapter finds Corman explaining how the post-war car boom, drive-in cinemas, and the appetites of teenagers carved a niche for his kind of movies. Or better said, how he fashioned a type of movie that would thrive in that world.

This revealing testimony reminds us how many things happen beyond the limits of the screen that condition and influence the exercise and consumption of art. It is hilarious how Hollywood apes his work and how ahead of the curve he tends to be.

Universal paid him to use the title of his early drag-race drama "The Fast and The Furious" (1954) for what was perhaps the most profitable franchise of our times. In 1994, way before "Spider-Man" (Sam Raimi, 2002), "Iron Man" (Jon Favreau, 2008), and the ascent of the MCU, he made a cheapie version of "The Fantastic Four" that was never officially released. Fans of Paul W.S. Anderson's "Resident Evil" movies will relish his stories about how he approached re-making Corman's "Death Race 2000" (1975).

The Hidden High-Art Tastemaker

Besides being a keen provider of popular entertainment, Corman was a shrewd distributor of foreign films in the U.S. market. His company, New World Pictures, regaled American audiences with many classics from top directors, including a string of Best Foreign Film Oscar winners like Ingmar Bergman's "Cries & Whispers" (1972), Federico Fellini's "Amarcord" (1973), Akira Kurosawa's "Dersu Uzala" (1975) and Volker Schlöndorff's "The Tin Drum" (1979).

It's a glaring blindspot in the documentary. Perhaps he had no creative input in those films, but making them available to audiences goes beyond a savvy business decision. There is a true love of cinema in his choices. You can complement your viewing of "Roger Corman: The Godfather of Pop Cinema" with an interview he gave to Criterion Channel's "Adventures in Movie Moviegoing." There is no high or low art with Corman. Just art.

Want to get an email when we publish new content?

Subscribe today