No "Marvel"?: The 2022 Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time Poll

Sight and Sound magazine founded The Greatest Films of All Time Poll in 1952. Since then, every ten years, the periodical edited by the British Film Institute asks filmmakers, critics, curators, and archivists to send their lists of the 10 greatest films of all time. How they define the greatest is entirely up to them. The leeway is an infinite chasm. To try to quantify art is a fool's errand. Why do we do this? For starters, it forces a sense of order into chaos and makes things manageable. It gives you a reference to navigate uncertainty. Neophytes can find their ground quickly. On the commercial side of things, inclusion on the list raises awareness which can translate into streams, sales of tickets, and physical media.

Every ten years, the results throw film culture into a tizzy. The just-released seventh iteration of the poll poured fuel into the dumpster fire of the current cultural war. We have a new number-one film, and it is a doozy. Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Chantal Akerman, 1975) displaced the hallowed Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958) to second place. In third place, you find Citizen Kane(Orson Wells, 1941). It held on to the top spot five consecutive times since 1962. The first-ever poll crowned Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948). Now, it is down to 41, tied with Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950).

Belgian director Chantal Akerman was only 25 years old when she made Jeanne Dielman. It was barely her second feature film - Je Tu Il Elle (1974) was the first. The title character, played by Delphine Seyrig, is a widow living in a gray, middle-class Brussels. She keeps her house and cares for her surly teenage son (Jan Decorte). Alone in the afternoon, she receives men in her apartment and provides them with sex. We follow her routine for three days. On the final day, an act of violence upends everything. The movie runs a stately 3 hours and 22 minutes. We observe Jeanne going about her day in long takes recorded with a fixed, unmovable camera. She cleans the house, cooks, and runs errands. The woman is precise and exacting, at least for a while. On the second day, her hair is messier, and she misses a button on her robe. On the third day, she cracks down, epically. The moment comes with the same restraint. It shocks twice as much.

Whether you are bored or riveted is beside the point. Jeanne Dielman challenges our conception of what a movie can and should be. It flies in the face of the tyranny of entertainment. Perhaps it is better to say the tyranny of distraction. Akerman uses cinema to shed light on the feminine universe, to submit us to its rhythms, and the stifling effect of modern domesticity imposed on women. It must be slow and contemplative to achieve the results Akerman seeks.

We have a Jewish woman behind the camera, a lesbian, to boot, concentrating her camera on feminine issues. To have such a film on top feels like a statement of purpose, compounded by the appearance of more recent films from filmmakers belonging to marginalized groups, that is to say, not white males:

There is Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Celine Sciamma, 2019), an incandescent period lesbian romance in 31st place. Moonlight (Barry Jenkins, 2016), the coming-of-age story of a gay black man, rests at 61. The racial horrors of Get Out (Jordan Peele, 2017) close down the list at 100.

Plenty of vitriol flies toward these movies. Some blame them for the disappearance of sturdy classics like Nashville (Robert Altman, 1975), Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959), and Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916). The fact that all 25 exiled films belong to white men of various nationalities seems to support the idea that an insidious woke agenda is at play. Writer and director Paul Schrader suggested as much in a Facebook post.

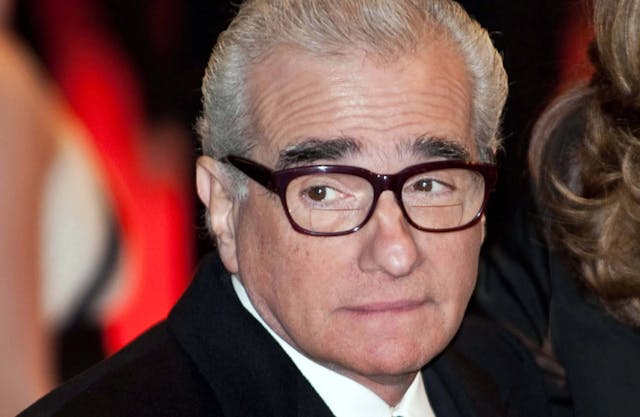

Schrader is a great artist. He wrote Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976), cozily perched at number 30 in the poll, but I think time is catching up with him. For one thing, Jeanne Dielman did not appear suddenly on the number one spot. In the previous 2012 poll, it shared a tie at number 36. It was one of only two films directed by women. The other was Beau Travail (Claire Denis, 1997), tied at 78. Ten years later, both films broke the top ten, and Akerman took the first spot. She even has a second film on the list, News from Home (1977) at 53. Overall, 11 films directed by women made the cut.

Schrader is correct about an expansion in the voting community. Last time, 846 people voted. This year, the BFI says 1636 did. Expanding the voting corps does reflect a historical continuum. More women and black artists are making movies. It is likelier that their works can make inroads into the canon. There are five films by black filmmakers on the list, with Do The Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) scoring highest at 25. How can this be a bad thing?

There is no objective way to assess art. Biases, preferences, prejudices, and ideological beliefs come into play. Their choices spring out of their ideas, values, and feelings. To pick Daughters of the Dust (Julie Dash, 1991) is not that different than deciding Citizen Kane (Orson Wells, 1941) reflects your idea of what a great movie is. The previous lists had fewer women and black filmmakers precisely because it mirrored the biases of the film industry at the time. The canon was white and male because most filmmakers were white and male.

Recency bias always comes into play. The older the movie, the hardest it is to get to it, even if it is a heralded classic. Check out the relative dearth of silent cinema. I am bothered by the absence of Les Vampires (Louis Feuillade, 1915), but its worth is not diminished by not getting a mention. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) may have fallen off the chart, but it still exists. And if you are lucky enough to live in the big city, you might even get a chance to catch a revival on the big screen.

Feminists did not gang up together and decided to stick it to Sam Peckinpah and kick The Wild Bunch (1969) to the curb because it is just too macho. Like any other poll, this is a snapshot of a moment in time, capturing whatever holds the mental real-estate in the mind of the voters. Its value resides in how it jumpstarts a conversation and brings awareness to worthy films. It may not be fair. It may not be complete. But then again, what is?

You can always find reasons to be annoyed. It bothers me that there are no films from Latin America. There is just one movie in Spanish - The Spirit of the Beehive (Victor Erice, 1973) - even though it is the fourth most-spoken language in the world. While we are tangentially talking about Spain, Pedro Almodóvar, Luis Buñuel, Carlos Saura, and Luis García Berlanga are no-shows. It is not the fault of Akerman. Nor any voter. The best we can do to correct these omissions is to spread the word about the films we love. A list of 100 titles cannot encompass the treasure trove of film.

Want to get an email when we publish new content?

Subscribe today